Photography as a profession

In the age of social media and constant distraction, Ansel Adams’s 1950s article makes me think what I am pursuing in photography today and whether I am following my own creative spirit.

background

I recently read an article titled The Profession of Photography, written by Ansel Adams and published by Aperture Magazine in 1952.

I want to share what I learned from Ansel’s thoughts on what defines a professional photographer, and my own reflections while reading it.

When I first started learning photography, the first two photographers I seriously read were Henri Cartier-Bresson and Ansel Adams.

They shaped the architecture of how I understand photography. Even now, whenever I feel confused or lost, I still return their books, looking for directions.

confused standards

Adams believes photography was as vital as other forms of communication and expression—painting, literature, music, or architecture.

Because of this, he argued that photography required serious standards of training; otherwise it would never reach its full position among the creative professions.

Yet he also admits that such standards were not easy to define.

That difficulty feels even sharper today.

As a young photographer, living in the age of social media, I often wonder what defines the value of my photographs.

Likes? Attention? Praise from peers?

I live in a world of confusion—a world of distraction—where sometimes I don’t even know what I am supposed to pursue.

Am I chasing more followers and likes?

Am I seeking more attention and exposure?

Am I imitating others until I eventually find my own style?

Or I’m searching for my own spirit?

I don’t have an answer.

training & school

In the essay, Adams emphasizes the importance of training.

He imagines photography schools not as mass-production lines, but closer to a conservatory method: fewer students, more individual attention, private assignments, and a deep grounding in the humanities discipline.

He further writes that mass instruction endangered the creative spirit.

Technique alone, in his view, was never enough. Observation and art training should be considered.

Adams concluded 10 requirements that a basic (photography) school should have.

- a strong foundation in the humanities

- adequate photographic theory and technique

- philosophical and aesthetic understanding of photography

- project-based, real-world problem solving

- combination with other arts and crafts

- awareness of the full reproduction process - from capture to print

- balance between personal expression and objectivity

- observe other arts and understand its aesthetic

- critical judgment without suppressing creativity

- engagement with the photographic community

amateur = love❤️

Adams believes that if one performs art, he must have the amateur spirit to the core of art itself, because amateur means love.

He mentions the greatest achievements were made by amateurs.

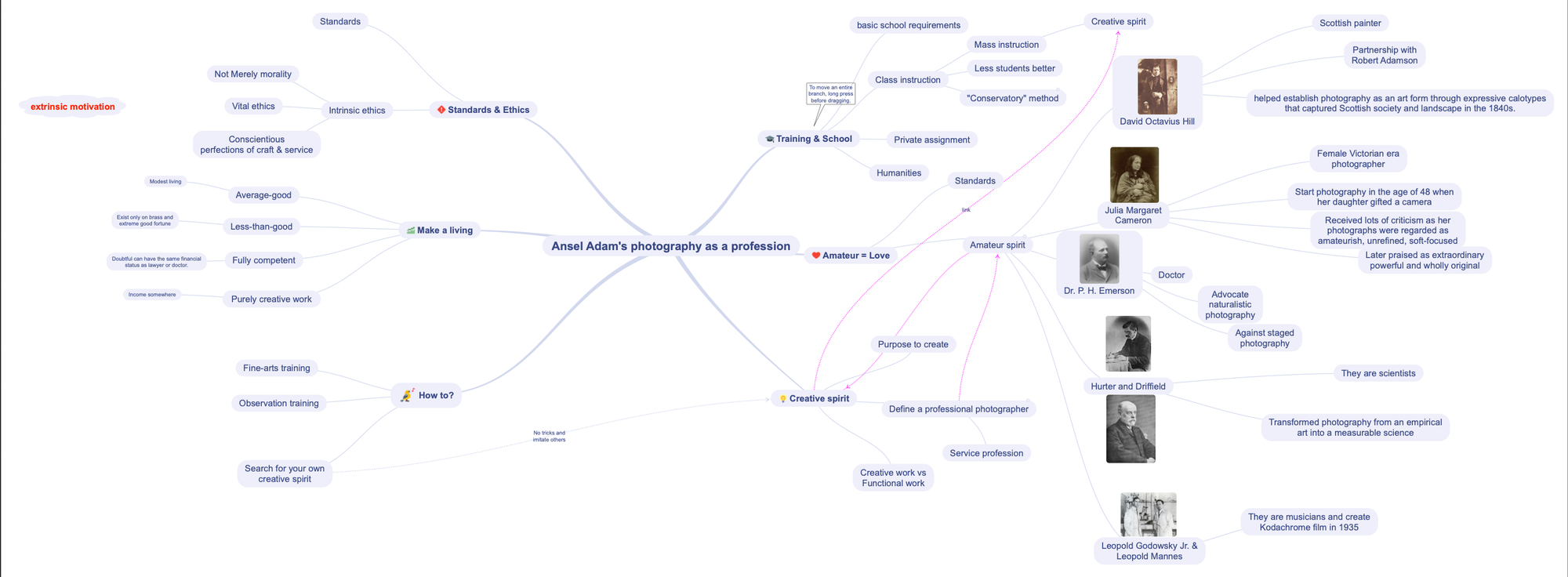

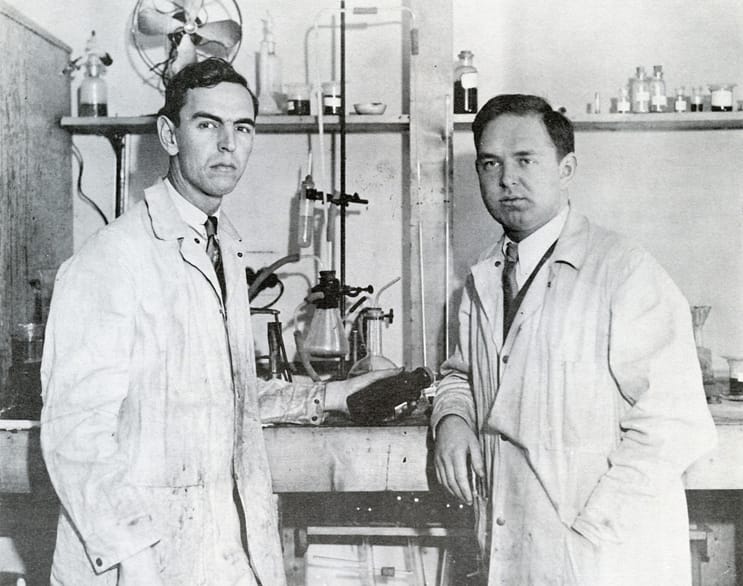

from left to right: David Octavius Hill, Julia Margaret Cameron, Dr. P. H. Emerson, Hurter, Driffield, Mannes and Godowsky

David Octavius Hill, a Scottish painter, helped establish photography as an art form through expressive calotypes that captured Scottish society and landscape in the 1840s.

Julia Margaret Cameron, a female Victorian era photographer, started photography in the age of 48 with a gifted camera from her daughter. She received lots of criticism as her photographs were regarded as amateurish, unrefined, soft-focused, but later praised as extraordinary powerful and wholly original.

Dr. P. H. Emerson, a British doctor, advocated naturalistic photography and redefined photography as an art form.

Ferdinand Hurter and Vero Charles Driffield, British scientists, transformed photography from an empirical art into a measurable science with the creation of H&D characteristic curve.

Leopold Godowsky Jr. and Leopold Mannes are musicians. They created Kodachrome, the first successful color-reversal film for still and motion photography in 1935.

Their backgrounds ranged from painters and scientists to musicians.

What united them was not professionalism in the commercial sense, but devotion.

what is “professionalism” in photography?

Even though Ansel argues service-based photography—work made according to client requirements—as not being “art,” photographers must still find a way to make a living through this kind of service.

So, what is the borderline between the creative amateur and the commercial professional, Ansel keeps asking.

Here, we can regard service professional and commercial professional as the same thing.

Ansel argues that the creative group can be functional group, but it’s hard for the functional group to be the creative group.

One must have the creative spirit to practice all fields of photography.

Any art relates to the creative spirit—which is constantly struggling to avoid desolation from within and without.

The profession of photography is regarded as both Service and personally Creative.

intrinsic ethics

Another thing I learn from Adam’s article is intrinsic ethics.

From Adams, standards and ethics are inseparable, and ethics are the social reflections of standards.

Adams redefine the intrinsic ethics are the ethics when no one is looking - these ethics are the frame and fabric of any true profession.

Adams continually argues that intrinsic ethics are vital ethics, which has nothing to do with billing or paying wages, but those relates to the conscientious perfections of craft and service, and those have their roots in a clean creative spirit.

But he also warns us that do not confuse the ethics with mere morality.

If we do what we should do because if we don’t, we burn, we are merely being expedient.

In other words, if we do what is considered right only because not doing so would bring punishment, it isn’t true morality — it’s just self-preservation.

How many photographers can honestly rise and say "I have practiced intrinsic ethics in all expressions of my profession?”

This part of paragraph struck me.

It reminds me that one day I will face moments when my personal spirit conflicts with external pressures—and I will have to pick a path.

[although I haven’t been in such a difficult situation, future I bet I will]

how to making a living in photography?

Adams writes that artists are struggling to live against the world.

He identifies four types of photographers who manage to make a living:

- average-good photographers → make a modest living

- less-than-good photographers → "exist only on brass and extreme good fortune”

- fully competent photographers → hard to remain financial status as other equivalent professions like doctors or lawyers due to lack of understanding and social recognition (I think in other words, fully competent photographers making a fortune are rare)

- not interested in commercial at all and only seek for pure-creative photographers → must have income somewhere

Adam’s advice is pragmatic - maintain a non-photographic vocation for income, while cultivating a personal photographic practice through serious art training.

We are too much dominated by all-or-none virtuosic concept of art.

In other words, Adams is against the concept of art that only views art in two states: either a sensational masterpiece, or nothing at all.

Technique alone is never enough. Photography must be nourished by fine arts training: observing more, looking at other photographers’ work, understanding other art forms, and discovering relationships between photography and other art forms.

"You don’t need to learn tricks or imitate others.” Adams replies.

Instead, search your own creative spirit.

For those curious about the structure of this post, or want to skip the reading content, I am sharing the mind map I used while writing it.

It outlines the path of my thinking at a glance.